|

The Chinese Abacus was an early aid for mathematical computations. Its only value is that it aids the memory of the human performing the calculation. A skilled abacus operator can work on addition and subtraction problems at the speed of a person equipped with a hand calculator (multiplication and division are slower). The abacus is often wrongly attributed to China. In fact, the oldest surviving abacus was used in 300 B.C. by the Babylonians. The earliest known written documentation of the Chinese abacus dates to the 2nd century BC.

Another possible source of the suanpan is Chinese counting rods, which operated with a decimal system but lacked the concept of zero as a place holder. The zero was probably introduced to the Chinese in the Tang Dynasty (618-907 AD) when travel in the Indian Ocean and the Middle East would have provided direct contact with India, allowing them to acquire the concept of zero and the decimal point from Indian merchants and mathematicians.

A publication of a French mathematical congress held in 1902 stated that the soroban replaced the use of bamboo rods at the end of the 16th century. According to Sal Restivo in Mathematics in Society and History: Sociological Inquiries (pp. 55-56) Chinese mathematics was in decline as Japanese interests were developing. "The scholar Mori Shigeyoshi [early to mid 17th century] who flourished in this period is Japan's first 'mathematician'. He is, according to legend, supposed to have traveled to China and returned with a knowledge of Chinese mathematical achievements and the suan-pan, a Chinese abacus. There is no historical basis for this story. The suan-pan was probably introduced to Japan much earlier. In any case, Mori was apparently a skilled manipulator of the suan-pan, known as the soroban in Japan . He taught the soroban arithmetic to many pupils, and may have written a text on the soroban, now lost." Two of Shigeyoshi's students wrote extant works which discussed the use of the soroban. Both wrote about square and cube root calculations and one of them also works on areas and volumes.

Suanpan arithmetic was still being taught in school in Hong Kong as recently as the late 1960s, and in Republic of China into the 1990s. However, when hand held calculators became readily available, school children's willingness to learn the use of the suanpan decreased dramatically. In the early days of hand held calculators, news of suanpan operators beating electronic calculators in arithmetic competitions in both speed and accuracy often appeared in the media. Early electronic calculators could only handle 8 to 10 significant digits, whereas suanpans can be built to virtually limitless precision. But when the functionality of calculators improved beyond simple arithmetic operations, most people realized that the suanpan could never compute higher functions, such as those in trigonometry, faster than a calculator. Nowadays, as calculators have become more affordable, suanpans are not commonly used in Hong Kong or Taiwan, but many parents still send their children to private tutors or school- and government- sponsored after school activities to learn bead arithmetic as a learning aid and a stepping stone to faster and more accurate mental arithmetic, or as a matter of cultural preservation. Speed competitions are still held. Suanpans are still being used elsewhere in China and in Japan, as well as in some few places in Canada and the United States.

In mainland China, formerly accountants and financial personnel had to pass certain graded examinations in bead arithmetic before they were qualified. Starting from about 2002 or 2004, this requirement has been entirely replaced by computer accounting.

|

HOME

HOME

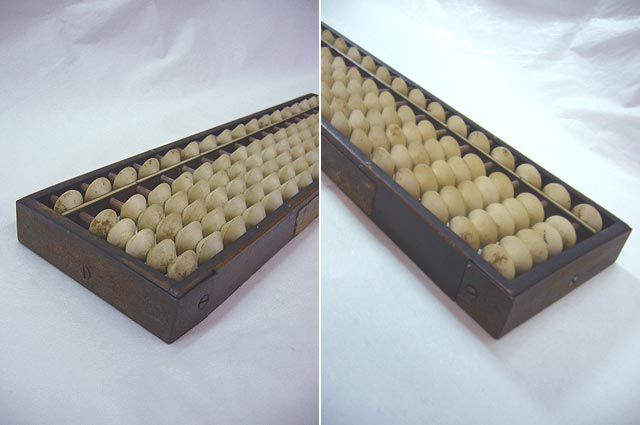

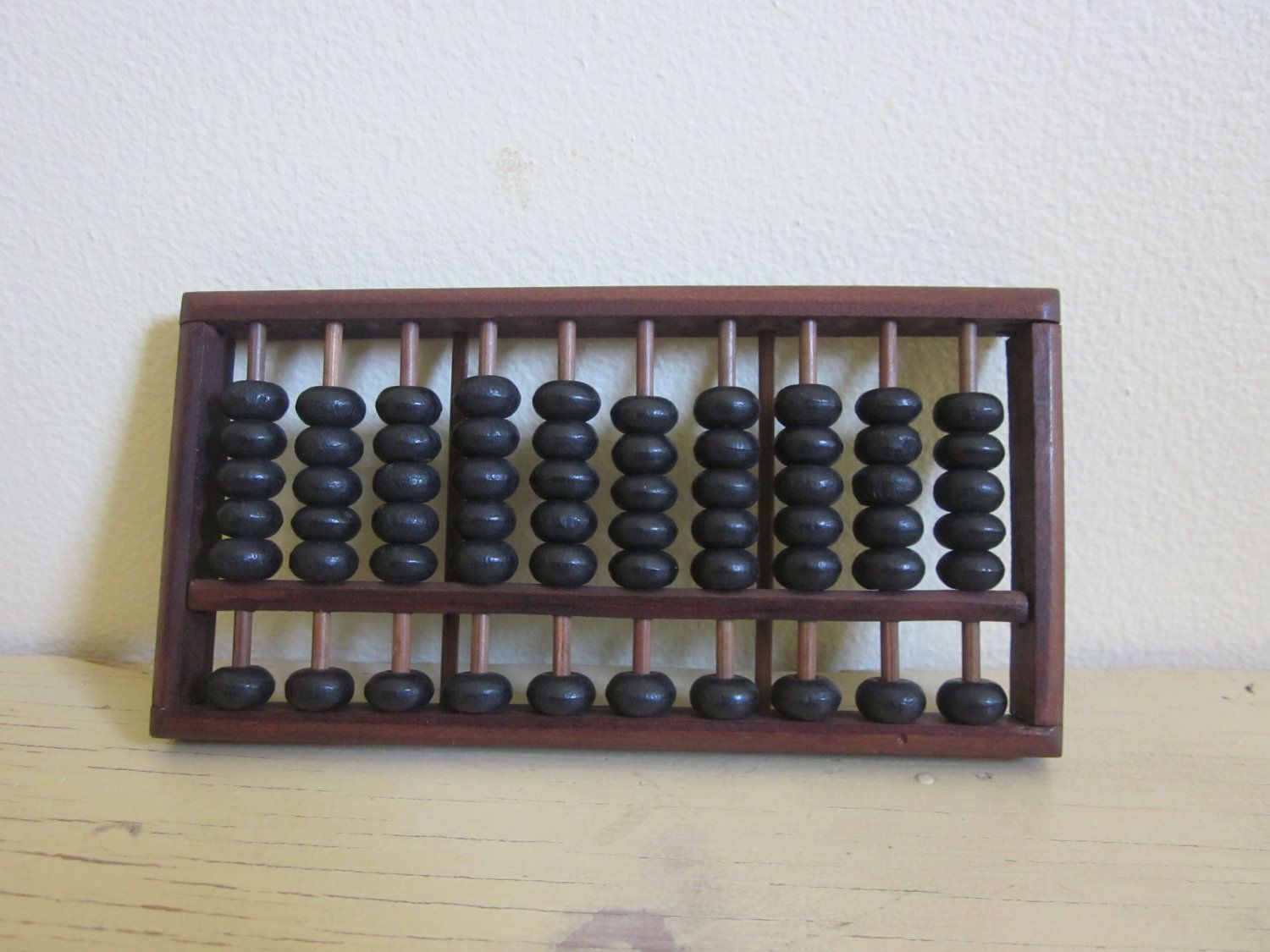

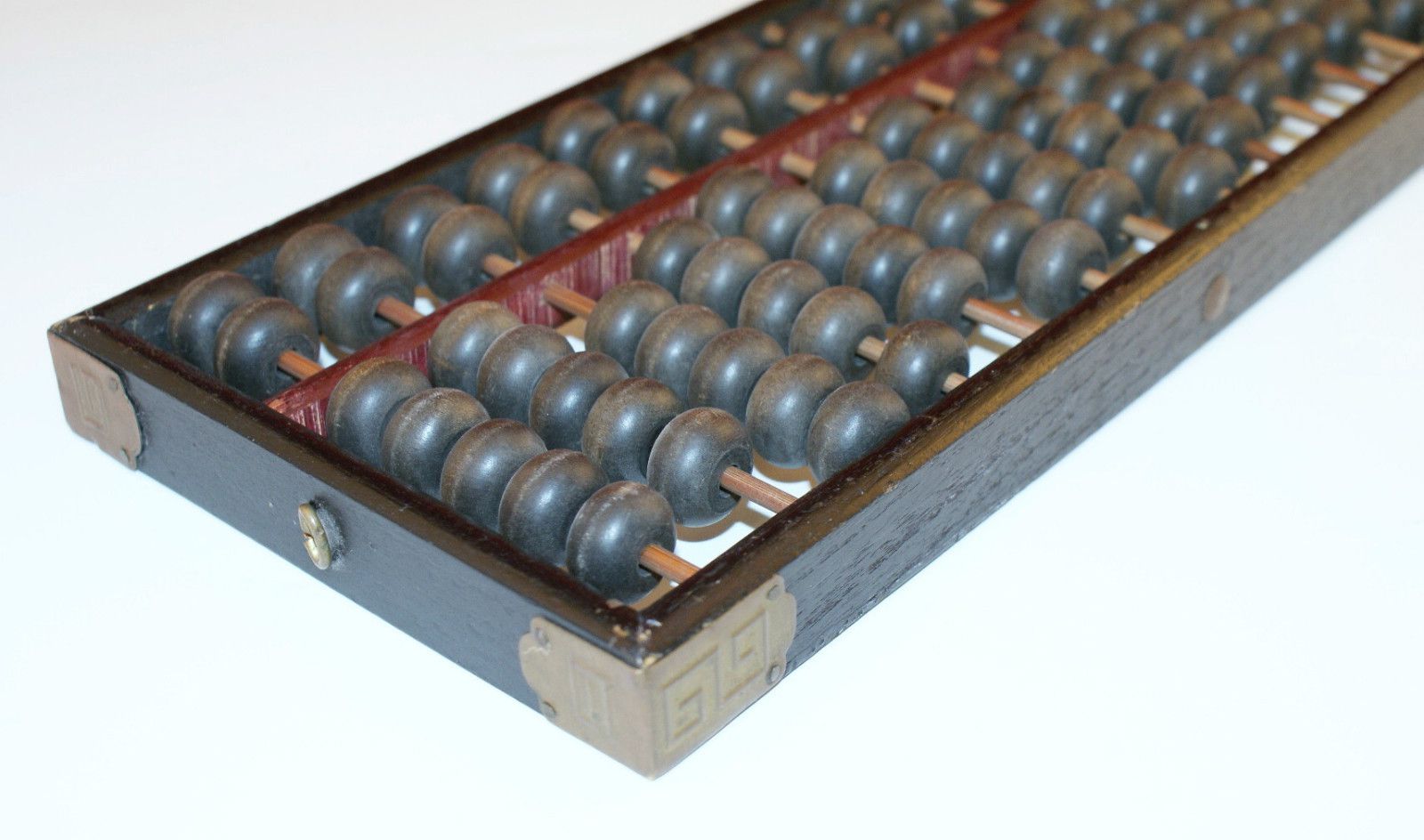

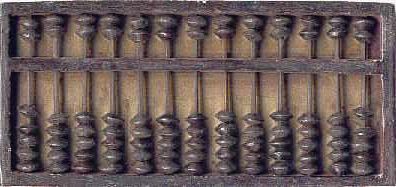

Lotus Flower Suan Pan 2/5 beads 15 digits

Lotus Flower Suan Pan 2/5 beads 15 digits